Portable Video Compressor

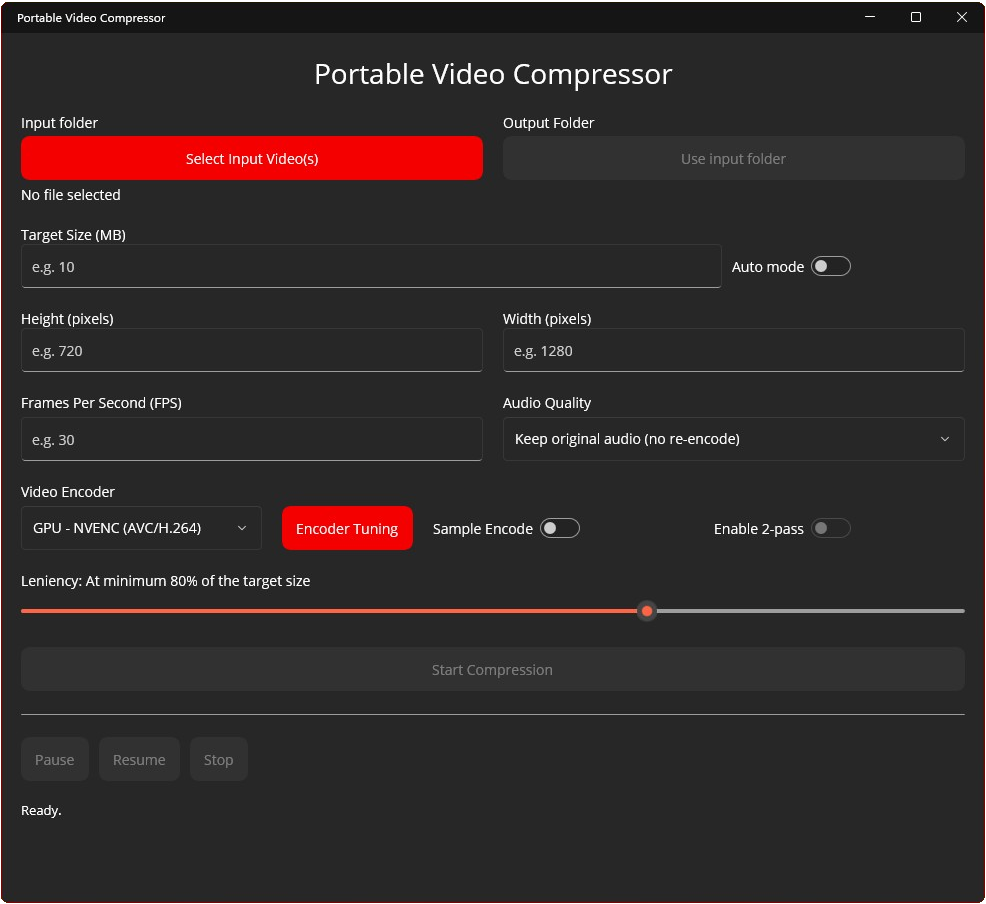

is a Windows desktop app that compresses video files into a user-chosen target size, it has a simple auto mode for quick turnarounds, and advanced tuning options for power users. It's built with .NET MAUI and wraps FFmpeg/FFprobe in a simple GUI for user convenience.

Version 1.0

Portable Video Compressor License

=================================Version 1.0 – 2025-12-07Copyright (c) 2025 PhotoRevisor

Contact: [email protected]

Website: PortableVideoCompressor.caAll rights reserved.1. Grant of UseYou are granted a non-exclusive, non-transferable, revocable license to:(a) download and use the Portable Video Compressor application ("Software")

free of charge for personal or internal use; and(b) view the Software's source code (where made available by the author); and(c) modify the Software's source code for your own personal or internal use.2. RestrictionsYou may NOT, without prior written permission from the copyright holder:(a) sell, resell, rent, lease, or otherwise charge any fee for access to,

use of, or distribution of the Software, whether in original or modified

form;(b) distribute, publish, or make publicly available the Software or any

modified version of it, whether in source or binary form;(c) rebrand, repackage, or otherwise represent the Software or any modified

version as your own product;(d) remove or alter any copyright notices, license notices, or third-party

notices included with the Software.3. OwnershipThe Software is licensed, not sold. All rights, title, and interest in and to

the Software, including all intellectual property rights, are and shall remain

with the copyright holder, except for third-party components which are subject

to their own licenses as described in the "Licenses" and "THIRD-PARTY-NOTICES"

files distributed with the Software.4. Third-Party ComponentsThe Software uses third-party components (including but not limited to

FFmpeg/FFprobe, .NET / .NET MAUI libraries, and Open Sans fonts) which are

licensed under their own terms (such as GPL, MIT, and OFL). Your rights to

those components are governed by their respective licenses, which are included

in the Licenses directory and/or referenced in THIRD-PARTY-NOTICES.Nothing in this license is intended to limit or restrict your rights under

those third-party licenses.5. No WarrantyTHE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR

IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY,

FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, AND NON-INFRINGEMENT.IN NO EVENT SHALL THE COPYRIGHT HOLDER BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES, OR

OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT, OR OTHERWISE,

ARISING FROM, OUT OF, OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER

DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.6. TerminationThis license is automatically terminated if you violate any of its terms.

Upon termination, you must stop using the Software and destroy all copies in

your possession. Provisions which by their nature should survive termination

shall survive, including but not limited to the disclaimers and limitations of

liability above.7. DonationsYou may voluntarily support the development of the Software through donations,

but donations do not grant any additional rights beyond those stated in this

license.

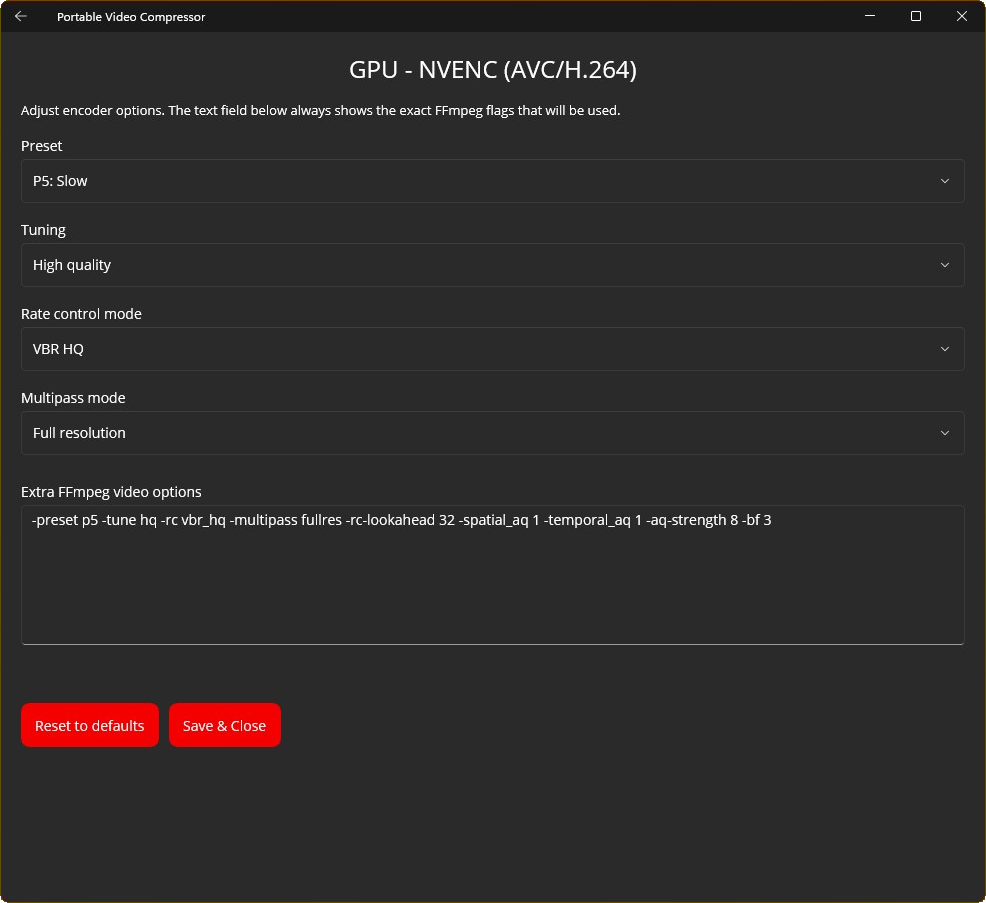

Here’s the backstory on why and how PVC happened:I started making Portable Video Compressor because I kept running into video file size limits and needed a reliable way around them. There are tons of video compressors out there—free and paid—but weirdly, not many let you aim for a specific file size as a hard target. I only knew of one that did, and honestly, it had enough annoying issues (and missing “this should be included if I’m paying” features) that I couldn’t justify the cost.So I finally went, “Fine. I’ll build it myself.” Which sounds confident… except I had basically zero coding experience and had never touched Visual Studio before. Like, absolute rock bottom.The first version of PVC was literally a tiny Windows batch script, 1.03 KB of, objectively, terrible garbage. You couldn’t change anything. It was hard-locked to 10 MB, 720p, 24 fps, and the audio bitrate was basically “whatever scraps are left,” which meant it came out garbled a lot of the time. Still, it proved the main thing: the idea actually worked in real life, even if that implementation was a dumpster fire.After that, I moved on to a real GUI prototype. After many AI-assisted hours, I got something working… but it still wasn’t great. The main upgrade was that I could finally change resolution and FPS. Audio controls and presets weren’t even a thing yet. And the sizing math? Brutal. It would massively undershoot the target, or overshoot it, then retry, and somehow make things worse. Fixing that with zero experience was a journey.Eventually, I got the size calculation to behave more reliably… kind of. It could still miss the target a bunch of times in certain cases—like, up to nine retries before it gave up... So that became the next thing to fix. After more AI-assisted work, it “worked”… about half the time. After even more hours (and some very colorful language), it finally reached the point where testing it didn’t make me want to disassociate from reality.One thing I noticed was the first estimate often landed about 20% off the target—either under or over. That got me thinking: what if I embraced that and let the user choose how strict it should be? At first, it felt wrong, because 20% could mean wasted quality. But realistically, if it’s 20% off, you’d want it to favor undershooting anyway. And sometimes you would trade time for slightly better quality. That’s basically how the leniency slider was born.Next up: audio. I added audio options (they’re still fairly minimal in 1.0) and changed the priority so the app protects audio quality first. I’ve got a film background, and it’s pretty well known that people will tolerate video looking rough as long as the audio is good, within reason of course.At that point the UI was getting out of control. Like, “this doesn’t even fit on my 1440p monitor” out of control. So I focused on restructuring it and making it actually look decent, which was way harder than it should’ve been. The dumbest part was getting active buttons to follow the user’s Windows accent color correctly. Once that was solved though, things finally started feeling smoother.Then I started adding encoder settings, and Visual Studio updated itself without asking. The project basically broke overnight. I spent three days trying to fix it, never figured out what the problem was, and ended up creating a brand-new project and copying all my code into it. Not fun.Once I was back on track, I started building encoder presets—and then realized I needed an AMD GPU to test AMF. Nobody I know has one, so that was… a head scratcher. I eventually found an AMD “GPU,” if you can call it that: my laptop’s integrated Ryzen graphics. So if AMF isn’t as solid as NVENC, I promise I did what I could. It was tested on a potato afterall.Somewhere around there, the math died again and I had to redo it (I think for the fourth time). The bright side is it improved from around 80% accuracy to about 90%, so I’ll take the win.After many more AI-assisted hours, I finally had something that looked decent and mostly worked perfectly with zero issues whatsoever.I’m kidding.HEVC on CPU just refused to work. Turns out libx HEVC and AVC don’t share the exact same tuning profiles—most overlap, but not all—and I had hard-coded them as if they were identical. So I split them into separate backend settings, and somehow that fixed it on the first try. One of the rare moments in this project where something didn’t fight me.After that, it was “shipping” time: licenses, legal stuff, and making sure I wasn’t accidentally setting myself up to get sued into oblivion.Then I made documentation so people wouldn’t have to guess how the app works. It’s pretty self-explanatory (and by then it even had an auto mode), but still—good software should come with good docs. So I wrote a README, a User’s Guide, and a Technical Spec sheet for anyone curious about the source code. All three ship with the app so they’re always there.Last steps were the installer and a website for distribution. Thankfully those went smoothly, because by then I was kind of losing it.After finishing touches like icons and cleanup, it was ready to publish… and then I had the “oh right” moment: where am I even hosting this? Google Drive was the first idea, but it throws up that ugly “this might be a virus” warning screen, so that got dropped fast. After some digging, I landed on Dropbox, and so far it’s been the cleanest option.Overall, it was a pretty wild project to build from scratch. If there’s one thing I learned, it’s this: I’m very glad this isn’t my full-time job. I have a whole new level of respect for the people who do this kind of thing every day.